Revolutionizing Plant Breeding Using Computational Informatics

Computer Science faculty Tony Kusalik and Ian Stavness are working to revolutionize plant breeding using digital data, artificial intelligence, and machine learning techniques. The following article was featured on Radio Canada.

Improved Agriculture Thanks to Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence will soon be useful to agriculture. A team of researchers at the University of Saskatchewan is developing tools using this technology, which in the long term will facilitate the selection of the best seeds to grow. Growing crops that have a higher yield and require fewer resources or that are resistant to drought, heat and cold, that’s what people have been doing for thousands of years, by crossing the best plants. A team of about fifty researchers at the University of Saskatchewan is now attempting to speed up this process thanks to artificial intelligence.

Photos and Genes

Computer sciences professor, Ian Stavness, observes photographs of flowering canola plants on his computer. The number of flowers impacts the number of seeds, and consequently, the quantity of canola oil produced. However, counting the number of flowers for millions of plants is a painstaking exercise, which can be eased through an innovative technique of artificial intelligence, called deep learning. This technique will allow a quick targeting of the plants that present the highest numbers of flowers to be used for crossing purposes.

What is Deep Learning?

It’s a technique that relies on a network of artificial neurons that allow a program to learn to recognize an object or a specific pattern within a set of data. For example, we can “train” the program by submitting thousands of images of canola flowers. Each time, we indicate to the computer how many canola flowers there are. Once “trained”, the program will be able to “calculate” the number of canola flowers on new images.

“If low temperatures and droughts are expected due to the weather phenomenon La Niña, the experts will need to be able to quickly cross the plants that will be able to tolerate these conditions,” explains computer sciences professor, Tony Kusalik.

“This objective will be achievable by crossing the plants that present the right genes. But how can they be identified? Most of the morphological traits are coded by multiple genes that act together and are difficult to determine,” he clarifies.That is why, in another area of the University, his team is studying a different aspect of the issue: the genes.

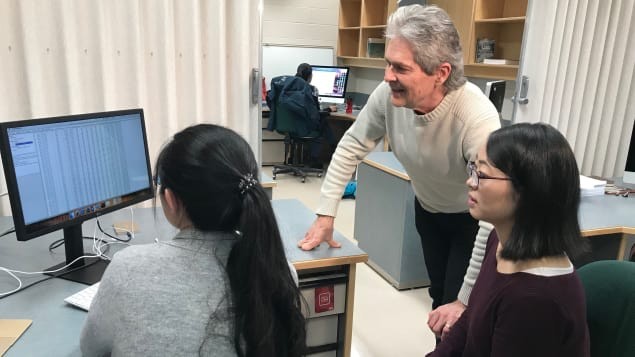

“We try to provide a bridge between the genes and the morphological characteristics of the plant,” explains computer sciences doctorate candidate, Logan Kopass. His colleague, post-doctorate candidate, Yan Yan, works with genetics data banks. In her computer, each small yellow dot indicates the presence of a gene. The blue dots indicate the presence of mutations on certain genes. These blue dots are potential prospects to explain the presence of a given character, such as the fact that a plant will flower sooner than another.

“How do we know that this mutation will have an impact on the flowering period?” she asks. “We can use this type of technology in order to find out.” This technology has indeed the capacity to analyze vast data banks, such as millions of A, G, T and C letters, which correspond to the nucleotides of DNA strands.

Sizeable Challenges

To locate information within these data banks, the technology of deep learning must analyze millions of cases. Therefore, the machine generally needs to analyze millions of photos of wheat to learn to identify wheat. However, there is a lack of data available. Establishing the genetic profile of a plant is very expensive. Photos are also costly, as more of them are needed than genotypes, and they require a tremendous amount of work since they are taken by drones, or by individuals holding a camera at the end of a stick or else using fixed cameras located in the fields.

The researchers are attempting to improve the performance of artificial intelligence tools to improve crossing efficiency. But they are not working alone. “It’s a multi-disciplinary project in which crop experts, engineers, computer scientists, synchrotron personnel and public policy experts collaborate,” says with enthusiasm, University of Saskatchewan computer sciences professor, Tony Kusalik.

The researchers hope that this project will be particularly useful to adapt crops to extreme events expected due to changes in weather patterns. “The information will also be useful for other studies in biology,” he concludes.

Full Article